Google, the police, and geofence warrants

A win for privacy, but not the riddance we need. Only Congress can provide that.

You may have seen the big news this week: Google announced it would shorten the retention period for users’ “Location History” in Google Maps, making it impossible for the company to access it, and denying law enforcement the ability to serve Google with “geofence warrants”, also known as “reverse location search warrants.” This is a good thing, as my issues with escalating warrantless surveillance of people who are neither suspects nor witnesses to a crime are well-documented. As investigative tools go, this flavor of search warrant flagrantly tramples upon the protections provided by the Fourth Amendment.

I’m no Google apologist, but as I've said for years, the company was never the bad guy here, nor was law enforcement, who just simply using lawfully available means to investigate crimes (we’ll talk about its abuse of these warrants in a minute). Congress allowed this mess to happen by doing nothing while modern tech continued to waltz pass the outdated Stored Communications Act (SCA).

Let’s talk about the four primary actors (not including the public) in the geofence warrant drama, going back to 2017: (1) lawmakers, (2) judges, (3) gov't/police, and (4) private sector firms w/location data.

Starting with (1). The Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA), of which the SCA is a part, was passed in 1986 and hasn’t had a major reform since. It seems every SCOTUS opinion in an electronic search case in the last decade+ has a paragraph excoriating Congress for not fixing outdated laws. Anyone upset about geofence warrants should probably start here.

Number (2). Judges don't like to make law from the bench, and they're bound by current Fourth Amendment precedent and case law. Worse yet, the 3-step process to get a geofence warrant relied on data anonymization as a safeguard against uniquely identifying innocent people. But we all know data anonymization is a fallacy, yet judges kept falling for it and signing off on these things. They shouldn’t have.

Number (3). If the claim is that government data-grabs are out of hand, then I agree. But put yourself in the position of a detective under pressure to solve a crime w/no suspects. If your superior was putting pressure on you to name a suspect and this tool was available, you’d use it. And use it they did: this, from Forbes …

Google doesn’t typically break down how many geofence warrants it receives, though it broke with tradition in 2021, revealing that more than 25% of the warrant requests it had received in the U.S. at the time were reverse location warrants. The volume of geofence warrants received by Google tripled from the end of 2018 to the end of 2019, reaching 3,000 warrants in a single quarter.

There is no doubt law enforcement abused the use of this investigative instrument. I heard a story years ago about a geofence warrant being used to crack a vandalism case involving a porta-potty. I mean, c’mon, that is ridiculous.

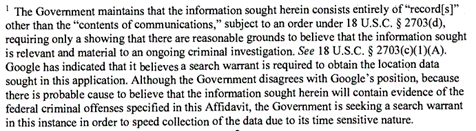

Number (4). Private companies with location data are an irresistible target for the gov't that wants that data, but the private sector has a business interest in being protective of user data for these kinds of activities. Here's an affidavit footnote in which law enforcement is complaining to the judge that Google is being uncooperative, saying an administrative subpoena (a 2703(d) order) should be good enough to get the data it wants. Google said 'no' and told detectives to go back & get a warrant.

It's not like this data was being handed out like Halloween candy. It was turned over in response to legal process.

There's plenty of blame to go around, but let’s close by talking about the media. Few people are engaging with social content relating to ECPA, SCA, Fourth Amendment, judicial review, or the subtle nuances of this discussion. But playing on Google's considerable brand recognition, combined with scary words like “dragnet” and phrasings about the company “helping the police”, is a fast path to click bait. It works. People assumed Google was somehow in cahoots w/the authorities to violate the public’s civil liberties, but that was never the case when it came to geofence warrants.

Lastly, let’s state the obvious: this new Google policy is not a substitute for government action. Google is self-interested and protective of its brand, which gets routinely battered on privacy. This is a business decision, not a public interest decision. Protecting the public interest is a job for Congress, and let’s not kid ourselves … Google may be the company with the biggest store of location data, but it’s definitely not the only one. Reporting suggesting that this is the end of geofence warrants is misleading. Even your car manufacturer has location data about you. As long as the law allows police to demand this data from whomever possesses it, geofence warrants will continue to exist.

/end