The Aviator

Congress should stop telling tech to grade its own homework and instead do what it was elected to do: make laws.

In 2004, Martin Scorsese directed The Aviator, a biopic starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Howard Hughes. The film interweaves multiple storylines from Hughes’ personal life and business pursuits, one of which was his ownership of the now-defunct airline TWA and its competitive battle with the also now-defunct Pan American Airways. At the time, Pan Am had a virtual monopoly on trans-Atlantic commercial flights, which the company attempted to cement by ghost-writing a bill sponsored by Senator Owen Brewster (R-ME), who had a close relationship with Pan Am CEO Juan Trippe.

Hughes obviously didn’t support the bill as he wanted TWA to have the opportunity to compete for those routes, so Brewster ginned up a sham federal investigation into Hughes to expose information that was that equal parts incriminating and embarrassing in an effort to extort Hughes’ public support of the bill. Hughes didn’t bite and was consequently hauled in front of Congress in 1947 to answer questions from Brewster and others on the Senate War Investigating Committee about war profiteering and the unethical means through which military contracts were won.

When pressed about whether Hughes Aircraft’s excessive wining and dining of Air Force officials rose to the level of “bribes”, Hughes responded, “I suppose you could consider them bribes, yes”.

Hughes explains to Brewster how the aviation business works and how this is common business practice and that all the major aircraft companies do it. But he goes on the offensive when he reminds Brewster that this practice, as unsavory as it seems, isn’t technically illegal. Hughes drives home the point:

I don’t know whether it’s a good system or not, I just know it is not illegal. You, Senator … you are the lawmaker. If you pass a law that states no one can entertain Air Force officers, well hell, I’d be happy to abide by it.

There’s more in this storyline relating to industry capture of a sitting Congressman, so if you have 8 minutes to spare, the scene is highly entertaining. Alan Alda is brilliant as the corrupt senator, bought & paid for by a powerful corporation and now put on the back foot on live TV by a witness who brought receipts.

What does this have to do with the tech industry? Congress has made quite the sport out of summoning tech execs to appear before Brewster-style Congressional committees and excoriating them on camera for everything from privacy abuses to offensive content to spreading misinformation. For the most part they deserve it, but also … most of these transgressions one could categorize as “awful but lawful.” I’ve watched many of these hearings over the years, and lawmakers typically don’t use such venues to accuse a publicly held company of breaking the law and suggest the witness is exposed to criminal liability. Mostly, the airing of grievances is a ritual humiliation that ends with lawmakers pressing industry executives to publicly support whatever bills they happen to be sponsoring. Nothing substantive is achieved. Everyone’s time is wasted.

The public’s overarching takeaway from these theatrical proceedings is that these companies cannot be trusted to protect the public interest, but that’s the problem – it’s not really their job. In a free market, these firms exist to prioritize the interests of shareholders, while lawmakers assume the responsibility of protecting the interests of the public as a counterweight to corporate profit-seeking. As callous and mercenary as it sounds, that’s the way the capitalist system is supposed to work.

So, do any of these executives have the courage to remind lawmakers that in fact *they* are the ones responsible for passing laws that make the things they complain about illegal? No, they don’t … they fold like an accordion. “Senator, thank you for your question. We’re committed to privacy, sustainability, fairness, blah, blah, blah, and we have our best people working on these problems.”

At some point I would love it if someone, anyone went after these elected officials the way Hughes went after Brewster and asked them why they’re not doing their job. Why do we still, in the year 2026, have no comprehensive privacy legislation in the U.S.? For all of your myriad issues about AI, why have you, Senator, aligned with administration policy to quash efforts to regulate it? You’re the elected lawmaker … go ahead, make some laws and we’ll follow them. In the meantime, the privacy intrusions, data brokering, and AI-generated slop that you find so offensive will continue because, like it or not, those things pay the bills at my company.

I think we all know the reason this doesn’t happen. It’s because these businesses don’t want to be regulated in a way that threatens profits or imbalances the playing field. I’ve described this before as a Nash Equilibrium, where each player in a noncooperative game does not deviate from his/her profit-maximizing strategy because all the other players are doing the same. There is no incentive to alter course and go on the attack in a Congressional hearing. Everyone is on the same page: maintain the status quo. Companies get the benefit of remaining unregulated while Congress gets the benefit of shifting the blame for societal harms onto companies that a lot of Americans don’t like anyways.

I’m not excusing corporate misconduct, but the business world’s prioritization of shareholder interest is literally why companies exist. None of these firms has any incentive to leave shareholder value on the table to protect the interests of society. They are profit-seeking entities that are free to chase monetary gains any way they want as long as they comply with laws and regulations. When laws and regulations are weak, we’re stuck where we are today: awful but lawful corporate conduct, satisfied shareholders, and ineffective lawmakers trying to bully firms into deviating from their profit-maximizing strategies to protect the constituents that they themselves were elected to serve.

It’s worth noting that there is some merit to the outrage that motivates these public spectacles. Tech companies are credibly accused of being responsible for some very, very bad things, like selling suicide kits online, addicting young people to social media, encouraging self-harm, exposing children to inappropriate content, and failing to protect kids from escalating threats of sexual predation on their platforms, often using Section 230 protections to shield themselves from legal liability. These things are obviously appalling. Whether they affect stock prices is a different matter. However, it’s important to remember we have to two justice systems in the U.S.: criminal and civil. Even if no criminal statutes are implicated (i.e., the conduct is awful but lawful), the civil court system is still available for a private plaintiff to bring a cause of action and seek damages, which is happening with all of the above-mentioned examples. Plaintiffs are even doing an end-run around Section 230 immunity by bringing product-liability claims.

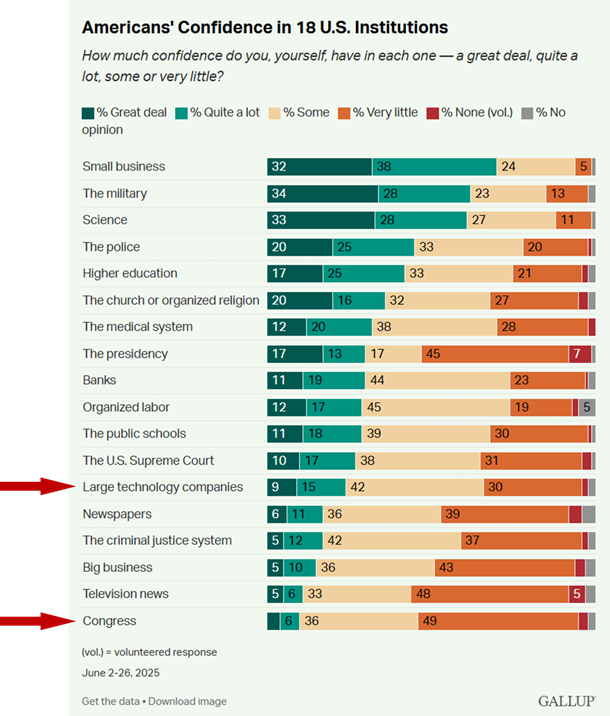

Congress needs to divert its time and attention to making law and/or amending existing law to protect the public from ever-evolving threats of harm. While industry’s aversion to publicly criticizing lawmakers for inaction is understandable, the public would likely welcome it. Congress is vulnerable. According to a June 2025 Gallup poll, Americans’ confidence in this esteemed institution continues to nosedive.

In a divided country, few things cross the partisan gap and provide the opportunity to unite, but accountability seems to be one of them, as it transcends business, politics, sports, and personal relationships. It’s a first-order principle like safety and security, and it creates an opening for businesses to remind people, as uncomfortable as it may seem, that shareholders rule the roost in the capitalist system they love so much, and it’s government’s job to ensure things don’t get out of hand.

I’ll close by stating the obvious: posting on the internet without a huge following often feels like shouting into the void. But it’s my hope that this article finds its way to *just one* future witness who’s inspired enough to gather fair-game oppo on committee members and come prepared to defend him/herself, their company, and their shareholders. Too many members of Congress are tangled up in solicited campaign donations, questionable stock trades, conflicts of interest, acceptance of corporate hospitality, legislative interests that favor a witness’ competitors, etc., etc. You don’t need a private investigator or FOIA requests to find this information … it’s all public.

Firms that personify corporate greed are surely flawed messengers for this sort of thing but given the state of distrust in media (which is currently optimized for continued access by not rocking the boat), we wouldn’t be any worse off seeing a corporate executive shine some daylight on these time- and taxpayer money-wasting theatrics. The tech industry should borrow a page from Howard Hughes and ask the most fundamental of questions: if you don’t like what I’m doing, then why haven’t you passed a law making it illegal?

/end